Having been the product manager and “systems guy” for the MPEG-H immersive audio codec as well as involved in multichannel AAC, I’ve seen a lot that can go wrong with the LFE channel. Plus, it is unnecessary – putting bass in the main channels is much more reliably reproduced than bass using the LFE channel.

Let’s look back at the problem the LFE channel was designed to solve. In the days of analog film, productions needed more bass in cinemas for dramatic effect, and the predecessor to the LFE channel was invented to provide it given the limitations of film sound tracks at the time. This channel was connected directly to additional bass speakers and was operated with 10 dB of extra gain so the bass could be appropriately loud when needed. When we moved from analog film tracks to digital cinema sound, this extra channel became the LFE channel. I think this probably works well in theaters where the sound system is carefully specified, installed, and tested. Tom Holman explains the evolution in his book “Surround Sound: Up and Running”.

Today in consumer playback, we are not constrained by the limited dynamic range of a magnetic or optical analog film soundtrack. All digital audio codecs are floating point inside, and have 500 or 600 dB of dynamic range internally. Their output is converted by 24-bit DACs with 120 dB of range. We don’t need a +10 dB boost on a separate channel anymore.

But, if it works, why not keep using it? Because in non-theatrical (consumer) equipment there are often implementation mistakes or omissions, and many creatives don’t mix in a Hollywood dubbing stage where the monitoring system is set up properly. There are mistakes in production and in playback devices. There are also some surprises lurking.

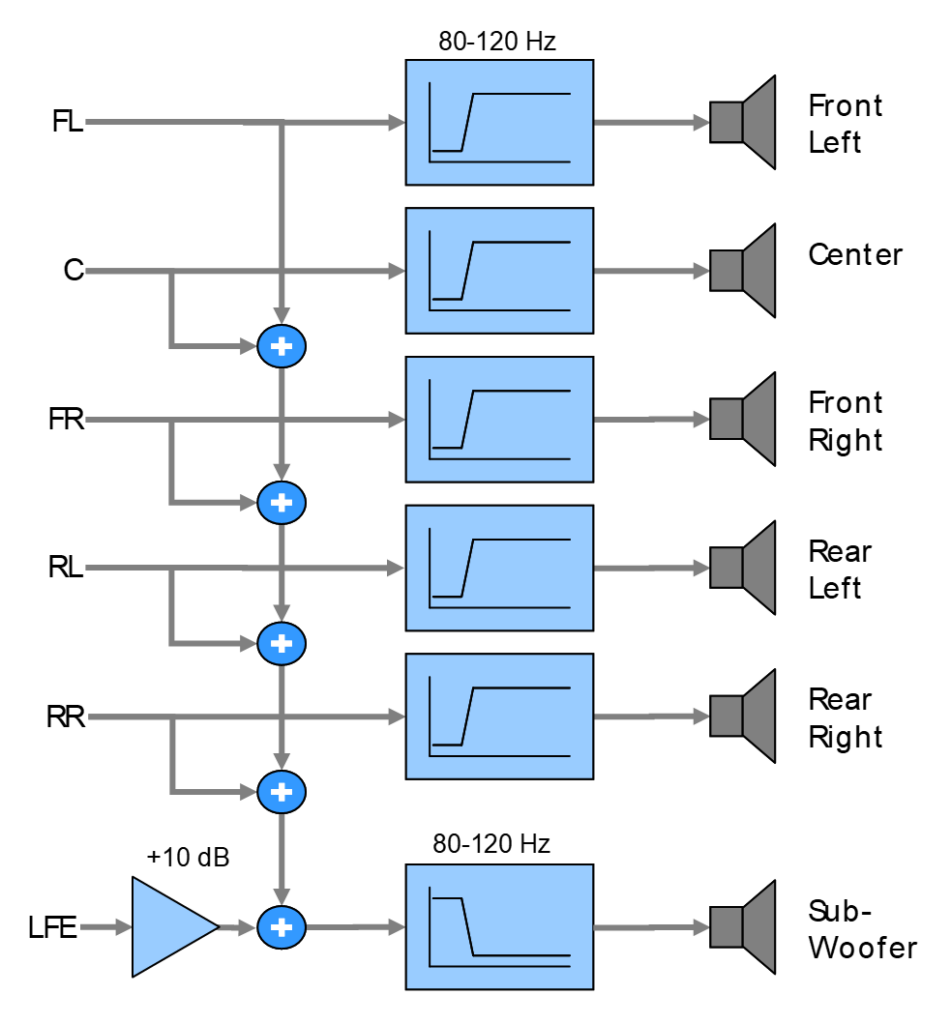

The diagram below shows how the LFE channel is supposed to work in a “bass managed” playback system. Bass below a crossover frequency in the main channels is routed to a subwoofer. The LFE channel is amplified 10 dB and also fed to the subwoofer.

Not shown in this diagram is what happens inside the codec. There the LFE channel is sampled at about 250 Hz. Typically, the encoder includes at least a 24 dB/octave low-pass filter at 120 Hz at its input to prevent aliasing, just as is done at about 20 kHz on the main channels. Thus, the LFE channel bandwidth through the codec is 120 Hz.

The most important point from the diagram is to realize in consumer systems, the LFE is not “the subwoofer channel”. The subwoofer is also being fed bass from all the other channels after decoding.

The first set of potential mistakes happens in setting up the +10 dB gain for a monitoring system in the mixing room. This +10 dB gain at the playback device has to be duplicated in the mix monitoring system. Some users are oblivious to this at first – they plug a subwoofer into their console’s or interface’s output for LFE and assume there’s nothing else needed. More experienced mixers (unless they have huge mains) will route all their channels through the subwoofer so its bass management sends all low bass to the subwoofer. Professional subwoofers often have a +10 dB switch that needs to be remembered to be set to amplify the LFE signal just as for consumer playback.

What if another engineer uses this room who is not experienced with surround sound? He’s read the LFE must be boosted by 10 dB, so he does that in the DAW. It sounds better on his mix, so that must be correct, right?

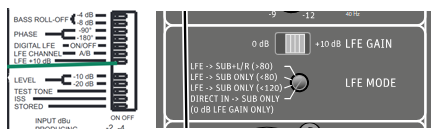

A similar problem occurs if you try to use a Blu-ray player in the mix room. The player’s LFE jack will have the 10 dB gain included by default unless you change its settings. If you leave the 10 dB boost in the subwoofer, you now have 20 dB of boost.

There’s also a subtle error in the diagram above. Everything is fine if all the filters corner at 120 Hz. What if they are at 80 Hz? The way the diagram is drawn, the LFE would be limited to 80 Hz, not 120 Hz. There’s a more complex diagram in fig. 2-14 of Holman’s book that shows how this should be correctly implemented. What if a speaker is just “plugged in the console” without bass management of a professional subwoofer? Well a consumer subwoofer might start to roll off at 150-200 Hz instead of a strong limit to 120 Hz.

Look at the gray panel in the switches illustration. I don’t use that brand and was surprised to see a four-position switch. If you read the manual and have the proper background, you can understand which setting works best in your situation. Are you certain?

So, assume that, despite all these issues the mixer gets a perfectly calibrated room and system and he’s eager to use the LFE channel for the bass line or explosion in his/her content. Will it be heard correctly by consumers? That depends.

If the consumer plays back a surround or immersive bitstream on an AVR / speaker system or a premium soundbar (say one around $1500), the answer is probably yes. Decoder manufacturers include certification tests to ensure this.

If the consumer listens to the surround stream on an AVR with stereo speakers with no subwoofer, the answer is no. Why? The LFE channel is discarded when the audio decoder downmixes to stereo.

It’s the same story if the consumer listens on a tablet or PC (with good headphones connected, otherwise there’s no bass anyway). The LFE channel is thrown away.

Now, what if Mrs. Consumer decides to listen on her phone using “spatial audio” rendering to her earbuds? Well, whoever programmed the binaural renderer could have decided to include the LFE or not. With the proper 10 dB boost, or not. There are no standards in this case. It could be anything.

So, there are plenty of use cases where the LFE channel is not heard. That’s why Holman said in 2008: “Do not record essential story-telling sound content only in the LFE channel for digital television”. Unfortunately, the consumer playback situation is considerably more complex today.

Holman’s book is very detailed on the LFE, spending ten pages on it, and he mentions two important secondary points. One is at high levels the ear is sensitive to small changes in very low frequency bass levels, as shown in the curves of ISO 226. So, dropping very low bass that is in the LFE can strongly affect mixes. The other is that directing the very low bass to a subwoofer reduces intermodulation distortion in the main speakers. (But with bass management, this happens with content in the main channels as well)

The Audio Engineering Society1 says:

The “0.1 channel” sometimes creates confusion for users of the standards described in the preceding when mixing sound that is not related to cinema applications. In such cases the assumption that it is necessary to generate a separate LFE signal in order to “conform to the standard” may be a distraction. It should be stressed that the generation of a separate LFE signal is entirely optional, and that in many music applications its use may even work against the requirement to generate an optimum degree of low-frequency envelopment.

I have heard from mixers that they must use the LFE because their customers “want to see all the meters moving” – I guess so that customers think a proper mastering job has been done. Well, show them this article and explain that if they want the best chance of hearing the content with the tonal balance intended, that LFE meter should read zero.

- AES Technical Council, Multichannel surround sound systems and operations, AES Technical Document, Document AESTD1001.1.01-10, 2001. Available from: http://www.aes.org/technical/documents/AESTD1001.pdf. ↩︎